Potential Spoilers Below

“Mat opened

his mouth to say it was enough, then hesitated as he noticed that the mayor was

talking quietly with a group of men. There were six of them, their vests drab

and ragged, their black hair unkempt.

One was gesturing toward Mat

and holding what looked to be a sheet of paper in his hand. Barlden shook his head, but the man with the paper gestured

more insistently.

“Here now,” Mat said softly.

“What’s this?”

“Mat, the sun . . .” Talmanes said.

The mayor pointed sharply, and

the ragged men sidled away. The men who had brought the food were crowding

around the dimming street, keeping to the center of it. Most were looking

toward the horizon.

“Mayor,” Mat called. “That’s

good enough. Make the throw!”

Barlden hesitated, glancing at

him, then looked down at the dice in his hand almost as if he’d forgotten them.

The men around him nodded anxiously, and so he raised his hand in a fist,

rattling the dice. The mayor looked across the street to meet Mat’s eyes, then

threw the dice onto the ground between them. They seemed too loud, a tiny

rattling thunderstorm, like bones cracking against one another.

Mat held his breath. It had

been a long while since he’d had reason to worry about a toss of the dice. He

leaned down, watching the white cubes tumble against the dirt. How would his luck

react to someone else throwing?

The dice came to a stop. A

pair of fours. An outright winning throw. Mat released a long, relieved breath,

though he felt a trickle of sweat down his temple.

“Mat . . .” Talmanes said

softly, making him look up. The men standing on the road didn’t look so

pleased. Several

of them cheered in excitement until their friends explained that a winning

throw from the mayor meant that Mat would take the prize. The crowd grew tense. Mat met Barlden’s eyes.

“Go,” the burly man said,

gesturing in disgust toward Mat and turning away. “Take your spoils and leave this place. Never

return.”

“Well,” Mat said, relaxing.

“Thank you kindly for the game, then. We—”

“GO!” the mayor bellowed. He looked

at the last slivers of sunlight on the horizon, then cursed and began waving

for the men to enter The Tipsy Gelding. Some lingered, glancing at Mat with

shock or hostility, but the mayor’s urgings soon bullied them into the

low-roofed inn. He pulled the door shut and left Mat, Talmanes and the two

soldiers standing alone on the street.

It suddenly seemed eerily

quiet. There wasn’t a villager on the street. Shouldn’t there be some noise

from inside the tavern, at least? Some clinking of mugs, some grumbling about

the lost wager?

“Well,” Mat said, voice

echoing against silent housefronts, “I guess that’s that.” He walked over to Pips,

calming the horse, who had begun to shuffle nervously. “Now, see, I told you,

Talmanes. Nothing to be worried about at all.”

And that’s when the screaming began.”

Note: Mat and his group had to fight and kill to make their

way out of the town only to return the following day. (I recommend that you read it)

“What is dead may never

die,”

“Mat shook his head slowly.

“No. Burn me, they’ve still got my gold. Come on, let’s see what he has to

say.”

“It started several months

back,” the mayor said, standing beside the window. They were in a neat—yet

simple—sitting room in his manor. The curtains and carpet were of a soft pale

green, almost the color of oxeye leaves, with light tan wood paneling. The

mayor’s wife had brought tea made from dried sweetberries. Mat hadn’t chosen to

drink any, and he had made certain to lean against the wall near the street

door. His spear rested beside him.

Barlden’s wife was a short,

brown-haired woman, faintly pudgy, with a motherly air. She returned from the

kitchen, carrying a bowl of honey for the tea, then hesitated as she saw Mat

leaning by the wall. She eyed the spear, then put the bowl on the table and

retreated.”

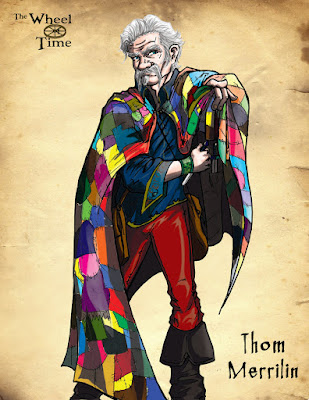

“What happened?” Mat asked,

glancing at Thom,

who had also declined a seat. The old gleeman stood

with arms crossed beside the door from the kitchens. He nodded to Mat; the

woman wasn’t listening at the door. He’d make a motion if he heard someone approach.

“We aren’t sure if it was something we did, or

just a cruel curse by the Dark One himself,” the

mayor said. “It was a normal day, early this year, just before the Feast

of Abram. Nothing really special about it that I can

remember. The weather had broken by then, though the snows hadn’t come yet. A

lot of us went about our normal activities the next morning, thinking nothing

of it.

|

| Representation of the Dark One |

“The oddities were small, you

see. A broken door here, a rip in someone’s clothing they didn’t remember. And the nightmares.

We all shared them, nightmares of death and killing. A few of the women started talking, and they realized

that they couldn’t remember turning in the previous evening. They could

remember waking, safe and comfortable in their beds, but only a few remembered

actually getting into bed. Those who could remember had gone to sleep early,

before sunset. For the rest of us, the late evening was just a blur.”

He fell silent. Mat glanced at

Thom, who did not respond. Mat could see in those blue eyes of his that he was

memorizing the tale. He’d better get it right if he puts me in any ballads, Mat

thought, folding his arms. And he’d better include my hat. This is a good

bloody hat.”

|

| Mat |

“I was in the pastures that night,” the mayor

continued. “I was helping old man Garken

with a broken strip of fencing. And then . . .

nothing. A fuzzing. I awoke the next morning in my own bed, next to my wife.

We felt tired, as if we hadn’t slept well.” He stopped, then more softly, he

added, “And I had the nightmares. They’re vague, and they fade. But I can

remember one vivid image. Old man Garken, dead at my feet. Killed as if by a

wild beast.”

Barlden stood next to a window

in the eastern wall, opposite Mat, staring out. “But I went to see Garken the

next day, and he was fine. We finished fixing the fence. It wasn’t until I got

back to town that I heard the chattering. The shared nightmares, the missing

hours just after sunset. We gathered, talking it through, and then it happened

again. The sun set, and when it rose I woke up in bed again, tired, mind full

of nightmares.” He shivered, then walked over to the table and poured himself a

cup of tea.

“We don’t know what happens at night,” the mayor said, stirring in a spoonful of honey.

“You don’t know?” Mat demanded. “I can bloody tell

you what happens at night. You—”

“We don’t know what happens,” the mayor interrupted, looking up sharply. “And have no care

to know.”

“But—”

“We have no need to know, outlander,” the mayor said harshly. “We want to live our lives as

best we can. Many of us turn in early, lying down before sunset. There are no

holes in our memories that way. We go to bed, we wake up in that same bed.

There are nightmares, perhaps some damage to the house, but nothing that can’t

be fixed. Others prefer to visit a tavern and drink to the setting of the sun.

There’s a blessing in that, I suppose. Drink all you want, and you never have

to worry about getting home. You always wake safe and sound in bed.”

“You can’t avoid this entirely,” Thom said softly. “You can’t pretend nothing is different.”

“We don’t.” Barlden took a

drink of tea. “We

have the rules. Rules that you ignored. No fires lit after sunset—we can’t have

a blaze starting in the night, without anyone to fight it. And we forbid

outsiders inside the town after sunset. We learned that lesson quickly. The

first people trapped here after nightfall were relatives of Sammrie the cooper. We found

blood on the walls of his home the next morning. But his sister and her family

were safely asleep in the beds he’d given them.” The mayor paused. “Now they

have the same nightmares we do.”

“So just leave,” Mat said. “Leave this bloody

place and go somewhere else!”

“We’ve tried,” the mayor said. “We always wake

up back here, no matter how far we go. Some have tried ending their lives. We

buried the bodies. They woke up the next morning in their beds.”

The room fell silent.

“Blood and bloody ashes,” Mat

whispered. He felt chilled.

“You survived the night,” the

mayor said, stirring his tea again. “I assumed that you hadn’t, after seeing

that bloodstain. We were curious to see where you’d wake up. Most of the rooms

in the inns are permanently taken by travelers who are now, for better or

worse, part of our village. We aren’t able to choose where someone awakens. It just

happens. An empty bed gets a new occupant, and from then on they wake up there

each morning.

“Anyway, when I heard you

talking to one another about what you’d seen, I realized that you must have

escaped. You remember the night too vividly. Anyone who . . . joins us simply

has the nightmares. Count yourselves lucky. I suggest you move on and forget Hinderstap.”

“We have Aes Sedai with us,” Thom said. “They

might be able to do something to help you. We could tell the White

Tower, have them send—”

|

| Aes Sedai |

|

| The White Tower |

“No!” Barlden said sharply.

“Our lives aren’t so bad, now that we know how to deal with our situation. We

don’t want Aes Sedai eyes on us.” He turned away. “We nearly turned your group

away flat. We do that, sometimes, if we sense that the travelers won’t obey our

rules. But you had Aes Sedai with you. They ask questions, they get curious. We

worried that if we turned you away, they’d get suspicious and force entrance.”

“Forcing them to leave at

sunset made them even more curious,” Mat said. “And having their bathing

attendants bloody try to kill them isn’t a good way to keep the secret either.”

The mayor looked wan. “Some

wished . . . well, that you’d be trapped here. They thought that if Aes Sedai

were bound here, they’d find a way out for all of us. We don’t all agree.

Either way, it’s our problem. Please, just. . . . Just go.”

“Fine.” Mat stood up straight

and picked up his spear. “But first, tell me where these came from.” He pulled

the paper from his pocket, the one that bore a drawing of his face.

Barlden glanced at it. “You’ll

find those spread around the nearby villages,” he said. “Someone’s looking for

you. As I told Ledron last night, I’m not in the business of selling out

guests. I wasn’t about to kidnap you and risk keeping you here overnight just for

some reward.”

“Who’s looking for me?” Mat

repeated.

“About twenty leagues to the

northeast, there’s a small town called Trustair. Rumor says that if you want

a little coin, you can bring news about a man who looks like the one in this

picture, or the other one. Visit an inn in Trustair called The Shaken Fist to

find the one looking for you.”

“Other picture?” Mat asked,

frowning.

“Yes. A burly fellow with a

beard. A note at the bottom says he has golden eyes.”

Mat glanced at Thom, who’d

raised a bushy eyebrow.

“Blood and bloody ashes,” Mat

muttered and pulled the side of his hat down. Who was looking for him and Perrin,

and what did they want? “We’ll be going, I suppose,” he said. He glanced at

Barlden. Poor fellow. That went for the entire village. But what was Mat to do

about it? There were fights you could win, and others you just had to leave for

someone else.

“They paid the iron price”

“Your gold is on the wagon outside,” the mayor

said. “We didn’t take any from your winnings.

The food is there too.” He met

Mat’s eyes. “We hold to our word, here. Other things are out of our control,

particularly for those who don’t listen to the rules. But we aren’t going to rob a man just because

he’s an outsider.”

“Mighty tolerant of you,” Mat

said flatly, pulling open the door. “Have a good day, then, and when night

comes, try not to kill anyone I wouldn’t kill. Thom, you coming?”

The gleeman joined him,

limping slightly from his old wound. Mat glanced back at Barlden, who stood

with sleeves rolled up in the center of the room, looking down at his teacup.

He seemed like he was wishing that cup held something a little stronger.

“Poor fellow,” Mat said, then

stepped out into the morning light after Thom and pulled the door shut behind

him.

“I assume we’re going after

that person spreading around pictures of you?” Thom asked.

“Right as Light, we are,” Mat

said, tying his ashandarei to Pips’ saddle. “It’s on the way to Four Kings

anyway. I’ll lead your horse if you can drive the wagon.”

|

| Mat holding his ashandarei |

Thom nodded. He was studying

the mayor’s home.

“What?” Mat asked.

“Nothing, lad,” the gleeman

said. “It’s just . . . well, it’s a sad tale. Something’s wrong in the world. There’s a snag

in the Pattern

here. The town unravels at night, and then the

world tries to reset it each morning to make things right again.”

“Well, they should be more

forthcoming,” Mat said. The villagers had pulled the food-filled wagon up while

Mat and Thom had been chatting with the mayor. It was hitched to two strong

draft horses, tan of coloring and wide of hoof.

“More forthcoming?” Thom

asked. “How? The mayor is right, they did try to warn us.”

Mat grunted, walking over to

open the chest and check on his gold. It was there, as the mayor had said. “I

don’t know,” he said. “They could put up a warning sign or something. Hello. Welcome

to Hinderstap. We will murder you in the night and eat your bloody face if you

stay past sunset. Try the pies. Martna

Baily makes them fresh daily.”

Thom didn’t chuckle. “Poor

taste, lad. There’s too much tragedy in this town for levity.”

“Funny,” Mat said. He counted

out about as much gold as he figured would be a good price for the food and the

wagon. Then, after a moment, he added ten more silver crowns. He set all of

this in a pile on the mayor’s doorstep, then closed the chest. “The more tragic

things get, the more I feel like laughing.”

“Are we really going to take

this wagon?”

“We need the food,” Mat said,

lashing the chest to the back of the wagon. Several large wheels of white

cheese and a half dozen legs of mutton lay prominently alongside the casks of

ale. The food smelled good, and his stomach rumbled. “I won it fair.” He

glanced at the villagers passing on the street. When he’d first seen them the

day before, he’d thought the slowness of their pace was due to the lazy nature

of the mountain villagers. Now it struck him that there was another reason

entirely.

He turned back to his work,

checking the horses’ harness. “And I don’t feel a bit bad taking the wagon and

horses. I doubt these villagers are going to be doing much traveling in the

future. . . .”

“but rises again, harder and stronger.”

“That had dried out the Mora at Merrilor and

let the Trollocs cross the river with ease. Grady could

open that dam in a moment—a strike with the One Power would open it up and release

the water from the canyon. So far, he hadn’t dared. Cauthon had ordered him not

to attack, but beyond that, he’d never be able to defeat three strong Dreadlords on his own. They’d kill him and dam the river again.

|

| Myrddraal leading Trollocs |

He caressed his wife’s letter,

then prepared himself. Cauthon had ordered him to make a gateway at

dawn to that same village. Doing so would reveal Grady. He didn’t know the

purpose of the order.

The basin below was filled with water, covering

the bodies of the fallen.

I guess now will do as well as

any time, Grady thought, taking a deep breath. Dawn should be almost here,

though the cloud cover kept the land dark.

He’d follow his orders. Light burn him, but he

would. But if Cauthon survived the battle downriver, he and Grady would have

words. Stern ones. A man like Cauthon, born of ordinary folk, should have known

better than to throw away lives.

He took another deep breath,

then began to weave a gateway. He opened it at that village the people had come

from yesterday. He didn’t know why he was to do this; the village had been

depopulated to make up the group that had fought earlier. He doubted anybody

remained. What had Mat called it? Hinderstap?

People roared through the

gateway, yelling, holding aloft cleavers, pitchforks, rusty swords. With them

came more soldiers of the Band, like the hundred who had fought

here before. Except . . .

Except by the light of the Dreadlords’ fires,

the faces of those soldiers were the same as the ones who had fought here

before . . . fought here and died.

Grady gaped as he stood up in the darkness,

watching those people attack. They were all the same. The same matrons, the

same farrier's and blacksmiths, the very same people. He’d watched them die,

and now they were back again.

The Trollocs probably couldn’t tell one human

from another, but the Dreadlords saw it—and understood that these were the same

people. Those three Dreadlords seemed stunned. One of the Dreadlords yelled out

about the Dark Lord abandoning them. He started flinging weaves at the people.

Those people just charged on,

heedless of the danger as many of their number were blown apart. They fell on

the Dreadlords, hacking at them with farming implements and kitchen knives. By

the time the Trollocs attacked, the Dreadlords were down. Now he could. . . .”

“Shaking off his stupor, Grady

gathered his power and destroyed the dam blocking the canyon.

And in doing so, he released

the river.”

Note: I shared this story to

show you that these two stories (The Wheel of Time & A Song of Ice and

Fire) share too many similarities to be coincidental. Like I have said on numerous occasions they

seem to be mirror

worlds of each

other. Did the authors corroborate with

each other on their books? I don’t

know? This story to me is metaphorically

the words of the Ironborn: “What is dead may never die, but rises again, harder and

stronger.” In case you missed it the first time the towns

people of Hinderstap died fighting the Dreadlords and Trollocs they ended up

face down in the water similar to the way the priests of the Drowned God drown their followers.

“The Drowned God shall decide

who sits the Seastone Chair,” the priest said.

“Kneel, that I might bless you.” Lord Merlyn sank

to his knees, and Aeron uncorked his skin and poured a stream of seawater on

his bald pate. “Lord God who drowned for us, let Meldred your servant be born

again from the sea. Bless him with salt, bless him with stone, bless him with

steel.” Water ran down Merlyn’s fat cheeks to soak his beard and fox-fur

mantle. “What is

dead may never die,” Aeron finished,

“but rises

again, harder and stronger.” But when Merlyn rose, he told him, “Stay

and listen, that you may spread god’s word.”

|

| Aeron |

“Three feet from the water’s

edge the waves broke around a rounded granite boulder. It was there that Aeron

Damphair stood, so all his school might see him, and hear the words he had to

say.

“We were born from the sea,

and to the sea we all return,” he began, as he had a hundred times before. “The

Storm

God in his wrath plucked Balon from

his castle and cast him down, and now he feasts beneath the waves.” He raised

his hands. “The iron king is dead! Yet a king will come again! For what is dead

may never die, but rises again, harder and stronger!”

|

| Balon |

“A king shall rise!” the

drowned men cried.

“He shall. He must. But who?”

The Damphair listened a moment, but only the waves gave answer. “Who shall be

our king?”

The drowned men began to slam

their driftwood cudgels one against the other. “Damphair!” they cried.

“Damphair King! Aeron King! Give us Damphair!”

Aeron shook his head. “If a

father has two sons and gives to one an axe and to the other a net, which does

he intend should be the warrior?”

“The axe is for the warrior,” Rus shouted back, “the net for a fisher of the seas.”

Comments encouraged. Love to hear the

ideas of others. Most believe that since I present my idea’s as “fact

like” I’m not open to change my viewpoints which is far from the truth. I

simply look at the information presented and go from there. If you can

shine a light on another way of thinking that opens the door to debate.

No comments:

Post a Comment